Synopsis

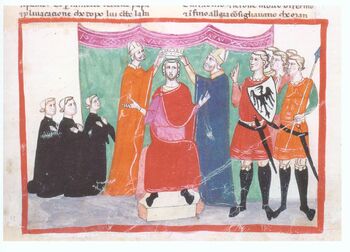

The Crowning of Manfred, King of Sicily. circa 1258

In thirteenth-century Florence, Italy, the pro-Papacy Guelphs have re-established supremacy and expelled the pro-imperial Ghibellines following the death of the Ghibelline Manfred, King of Sicily. The triumphant Guelphs await their champion, the French Charles d’Anjou, while their opponents await the arrival of young Corradino from Germany with troops sufficient to restore their power. During the victory festival that follows the Ghibelline return, Monna Gegia de’ Becari, a Guelph partisan, and her husband Cincolo, a Ghibelline, receive a visit from an androgynous Ghibelline named Ricciardo de’ Rossini, who declares his intention to leave Florence at dusk on a secret mission. They are joined by a master chess-player, Buzeccha, and a Guelph adherent named Giuseppe de’ Bosticchi, or Beppe, whose arrival nearly incites Ricciardo to violence. Once alone with Cincolo, Ricciardo reveals his mission: he will attempt to persuade the Ghibelline general Lostendardo to remain neutral in the coming contest between Charles and Corradino, and Cincolo will bear a letter from Ricciardo to Corradino. Ricciardo visits Lostendardo and reveals himself to be the female Despina, for whose love Lostendardo had killed Manfred. In her meeting with the general, Despina, who loved Manfred for his nobility and virtue, attempts to remind Lostendardo of the former love the general had for Manfred. Lostendardo executes Despina. Meanwhile, Cincolo bears the letter to Corradino, and we discover that Despina was Cincolo and Gegia’s foster daughter. Through treachery, Corradino is captured and executed by Charles, and Lostendardo displays to the condemned man the corpse of Despina laid out in a litter.

Historical Context

As inspiration for the story, Shelley draws on the actual historical Guelph-Ghibelline power struggle that characterized Italian politics for 400 years. The conflict began with the Investiture Controversy, an affair of church against state, in which Popes challenged the authority of monarchy over appointments, or investitures, of church officials. In 1122, the dispute ended with the Concordat of Worms, which allowed monarchies to invest Church appointments with secular, but not spiritual, authority. Although settled in the rest of Europe, the controversy continued in Italy with a division into the Guelph camp, which supported the Pope, and the Ghibelline side, supporters of the Holy Roman Emperor. Poet Dante Alighieri himself was a Guelph, and suffered exile after a Ghibelline occupation of Florence, Italy.

German influence persisted in Italy. Emperor Frederick II, a supporter of the Ghibelline cause, died in 1250. The chief supporter became Manfred, the King of Sicily, whose territory included not only the island, but the southern half of Italy, Naples being one of its cities. Manfred refused to surrender his kingdom to the Pope and became regent for the royal heir Conradin (Corradino); eventually he became patron of the Ghibelline League.Charles of Anjou ultimately executed Conradin in 1268.

Conflict

“Passions” is a narrative deeply rooted in the concept of conflict. Shelley uses struggle as a context with which to make statements about the various dimensions of love; passion; politics; and the public/private dichotomy, including domestic settings. Conflict occurs at diverse levels, some external, others internal and therefore not always so overt. It is these internal contests that interest Shelley just as much as the larger historical context.

There are periodic references to inner struggles, which Shelley locates not only in mind, but also through the body. in the bodily sphere. Gegia’s visage exhibits a “continual war maintained between her bodily and mental faculties” (Shelley 2) and a “spirit of contention” “fermenting” in her bosom (3). The warlike Lostendardo, a model of martial vigor, reflects inwardly what is an outward fact: “Every feature of his countenance spoke of the struggle of passions,” he exhibits “strong inward struggle,” and his forehead contains “a thousand contradictory lines” (11). For Shelley as for Lostendardo, struggle “speaks” its own discourse within the body, employs its own language and signifiers.

“Passions” implies that external, larger conflict is born in the body and its motions, and that we must look to the human body for the origin of all political division and contention; the smaller conflict is a mirror of the larger. The mind loses control, unable to exert rationality, and the body injects dispute into the world. In fact, Gegia’s mind-body division expresses itself in a politicization of the body, a “body politic” or physical turn to politics that parallels and mirrors the larger context of the tale; she laments that her “Ghibelline leg” prevents her from enjoying the festival (2). This limb has declared war on her body, indicating that the body itself has somehow absorbed the outer conflict from the mind in a political psychosomatization, or the body's reflection of mental movements, of partisan spirit. Moreover, it represents for her a somatization, or placement in the body, of the politics of her marriage; marital difference becomes part of her physical being.

The Chess Game

Conflict also arrives in the form of Buzeccha and his own passion, the chess game. As a plot device, the chess game Chess as a theme casts its shadow over the narrative as a method by which different “players” make their political “moves” on the chess-board that is Italy itself; in fact, Shelley marks the game out as the rational, logical, non-passionate, and non-violent counterpart to the violence in the current political environment. Employing military metaphors and language, Buzeccha characterizes chess as “the field of battle” (8) and a lost check-mate as a “mowing down” of the “rank and file” (9). The chess metaphor makes Cincolo as “pawn,” for Ricciardo calls him of “little note” (10); Ricciardo hopes to make a move and “capture” Lostendardo and, in a political chess-move, neutralize him.

Even profession falls under the sway of conflict as Shelley politicizes and injects passions into labor. Cincolo must “make shoes for Guelphs” (4); meanwhile, Buzeccha’s military phraseology turns the ordinary shoe into a locus of conflict: “every hole of your awl is a square of the board, every stitch a move, and a finished pair, paid for, check-mate for your adversary” (8).

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SPHERES, DIVISION, AND DOUBLING

Shelley employs the public/private binary opposition to treat the issues of passion, love, desire, and politics and how such themes might resolve inherent problems. Particularly, the private sphere and the domestic space become areas where characters settle Shelley’s questions about feeling and political spirit. Scholar Johanna Smith notes that the story "analyzes the effects of partisan political passions, and ... embeds these political reflections in a domestic plot" (59). In its portrayals, “Passions” shows us the larger historical context of a community contest and the figures whose public life represent intense emotion and partisanship. Lostendardo’s public existence exhibits a spiritually damaging picture for its practitioner: “From the moment [Despina] had rejected him, the fire of rage had burned in his heart, consuming all healthy feeling, all human sympathies and gentleness of soul. … The spirit, not of a man, but of a devil, seemed to live within him, urging him to crime … “ (17). Male passion and emotional extremity, for the tale a wasting disease, destroy feminine domestic qualities to the point that the warrior seems to lose the ability to act of his own will. One work observes that the warrior "suffers from extreme egotism and is completely given over to the imposition and realization of his own inclinations" (Mary Shelley 76). Bonnie Neumann notes this disease as something approaching madness that follows the "devil" in Lostendardo; both characters "are victims of war and revolution; but, in a more immediate sense, both are also destroyed ... by monomanical, Satanic insanity" (265). Lostendardo’s private love and desire for Despina have now become a new public love, of revenge and honor, a damaging self-love, rather than other-love, that spills out into the political sphere with fatal results. His “terrible egotism … would sacrifice [him] to the establishment of his will” (11). Shelley implies that passion and desire are potentially publicly destructive. It appears to be the role of the private and of domesticity to (re)assert reason and rationality, peace and calm into a highly-charged atmosphere.

In its opening scenes, “Passions” juxtaposes the city-wide partisan celebration with a domestic setting. Despite the intrusions of public political division onto its two adherents’ private life, Gegia and Cincolo practice their own politics of marriage, that of resigned and perhaps even grudging acceptance and the absence of any intense party passion that characterizes the world outside; the mutual interdependence that characterizes marital relationships overrides larger political feeling. In fact, the private relationship represents an “allegiance” that predominates over the party loyalties that operate in the public arena. For Shelley, the domestic sphere has brought a peace—indeed, a truce—that the external world would or could not, softening the intensity of public sentiment. She personalizes the dehumanization of the communal conflict with the private sorrow of a mother whose son Cincolo had compelled to serve the opposite party and who has sacrificed him to public bloodshed.

Domesticity affords the individual an opportunity to pacify passion with cool thought, for Cincolo remarks of their early married life: “[T]hose were happy times when there was neither Guelph nor Ghibelline. … [We] are two fools, and shall be more at peace under the ground than above it.” It is only that most private of spaces, the grave, which will resolve all issues of passion. Only when two strangers, Ricciardo and Beppe, from the outside enter the home do we see an intensification of political feeling that threatens the domestic peace. Shelley cleverly doubles the Guelph-Ghibelline division of the marrieds with two guests that provide a second political opposition; here we observe a stark contrast, Gegia and Cincolo representing the nonviolent half of political spirit and the guests the vehement part. Even so, Ricciardo feels the power of domestic settings to still his fury: “I do not come here to indulge in private sorrows or in private revenge” (10). Politics and party passion do not belong to the domestic space. Shelley implies that the cool temper of rationality reigns with a moderating influence in the private realm what appears unrestrained in the macrocontext of public passion.

A TRANSGENDER POWER-BROKER

As tropes, splits and doubling find their way into the description of Ricciardo/Despina, whose androgynous blend and ambiguous characterization become a critical epicenter for the blending or divorce of the public and private realms that underlie the tale and becomes a location for an ambivalence as to whether to follow love or politics. In "Passions," the male dress constitutes Despina's performance as political power-broker, which suppresses for a time her female tendency to focus on love once she sheds the male garb. Gerianne Friedline implies that the feminine performance of love-diplomat is hidden and must emerge at some point or remain unwhole: "[Stories such as "Passions"] expose damage below these paradigms [of ideals] and show us the flaws in defining ourselves based merely on appearances. ... [T]he corpus of her later fiction shows readers that external appearance is merely a means of packaging and presentation" (2). Here Shelley appropriates a female from her traditional occupation of the private and domestic sphere and thrusts her as a boy into the masculine-dominated world of public affairs and political movement; even more, a girl’s love for Manfred as a person has transgenderized into a political love for the dead king through emissaryship as a pseudo-male. Ricciardo’s very appearance reflects a curious, epicene combination of masculine and feminine qualities. While his face possesses “wonderful beauty,” his throat is “fair,” and his lips of the “deepest sensibility,” he projects the masculine qualities of “self-possession,” “dignity,” and “decision” of manner (5-6). Shelley blends in this one person the attributes of fineness, delicacy, and beauty with strength, power, and confidence.

As a female, Despina loved a man privately and secretly for his noble qualities, but as a male, Ricciardo now translates that love into the public campaign for his memory to achieve political ends. "Passions" characterizes love as a fluid, protean quality that can adapt itself to the private, domestic sphere as love for a person or quality as well as to the public arena as love for a philosophical idea. By her account, Despina characterizes her private affection for a man that approached the Platonic, the pure, the metaphysical, even the altruistic:

[I was a lover who] had already parted with her heart, her soul, her will, her entire being,

an involuntary sacrifice at the shrine of all that is noble and divine in human nature. My

spirit worshipped Manfred as a saint … . [T]he profound and eternal nature of my passion

saved me. I loved Manfred. I loved the sun because it enlightened him; I loved the air

that fed him; I deified myself for that my heart was the temple in which he resided.

…

[H]e lives in my soul as lovely, as noble, … as when his voice awoke the mute air … .

[T]hat small shrine that encase his spirit was all that existed of him; but now, he is a

part of all things; his spirit surrounds me, interpenetrates; … his death has united me

to him for ever. (12-13)

Shortly thereafter, Shelley tells us that the girl’s thoughts are “elevated to the eternity” of a star which she “worshipped” (15); love has risen above politics.

In the domesticity of a castle, Despina loved a man personally not only for his attractive and noble personal qualities, but also for how those traits transmuted him into an idealization of political virtue ; her love was a sublimated, non-sexual, non-physical, pure passion that seemed to reconcile both public and private. In fact, her “eternal” passion, which she has transcendentalized, or caused to rise above worldly concerns, contrasts with the ephemeral nature of worldly politics; private love “deifies” and sensitively observes the divine, while political and party spirit remain in the material realm of man. Moreover, she infuses the universe with human attributes, investing it with a Platonized love that has risen above materiality. Later, however, in the public sphere, Ricciardo expresses that love as “politicized love” in a ploy to access and remind Lostendardo of his own lost love; private love becomes political love and involves cunning and deceit in the proper execution of its ends. In fact, Despina, not entirely innocent of power-moves, attempts to use the former, forgotten personal love of Lostendardo for Manfred, as well as his desire for her, as a diplomatic leverage-point to effect a political and public objective and to alter the partisan landscape of Italy. “Passions” intimates that the true nature of love, its purity of essence, is to be found in the private domain, and that politics tend to defile and contaminate that purity. The female side of the stranger seems to represent love, the male side politics and its extremity of feeling. In fact, it is as the male Ricciardo that Despina encourages Cincolo to rouse and even feed his passion: “[I]f you feel any indignation at my fate, let that feeling attach you still more strongly to the cause for which I live and die” (10). Only in her restored femininity does Despina attempt to employ softer persuasion, rationality, and appeal to love rather than furor as a guiding motivation for action. As one work suggests, the male disguise represents the true nature--the political nature--of Despina that is her genuine subjectivity: "[Stories such as "Passions"] investigate the importance of outward markers, such as clothes, in determining selfhood" (Companion 168).

For Shelley, political drives and public passions tend to blind one to private feeling and innermost, deeper currents of love. Even in the intimate confines of his own domestic space, Cincolo is unable to penetrate the disguise that conceals his own foster-daughter and see the family bond that lay deeper than any surface political sympathy of and with a teenage boy. He laments the possibility that “in the disguise of Ricciardo I led her to destruction. … May these eyes be for ever blinded! … that knew not Despina in those soft looks and heavenly smiles. … [W]hy did I not read her secret in her forbearance [at Gegia’s tirade]? … I, blind fool, did not see the spirit of the Elisei in her eyes” (20-21). Political passion rendered Cincolo insensate to deeper feelings and discernment because of an overriding interest in his party’s supremacy. As a male involved in extra-domestic affairs of public concern, he was unable to distinguish the youth’s blurred identity. It is only the domestic half of the partnership, and one that remains at home, a woman such as Gegia (the nurturing mother whose very maternity brings her close with a child) along with her female friends, that experiences greater powers of insight in inferring a possibly doubled identity in the stranger.

LOVE AND DESIRE

Shelley presents us with two portraits of love and desire and locates those portraits within a political climate or context that has the power either to preserve and etherealize them or to corrupt them through base passion. Political spirit, she implies, can either distill love to an untainted essence or corrupt it with impurity; as such, partisan zeal contains within it creative and destructive powers over other emotive areas of the human being and the ability to intrude by its power from the public sphere into the private arena. Despina herself represents and becomes the performance of a purity of love and desire, a love that transcends physicality and physical craving. A politicized love drives her to create and project images of male rulers as idealized leaders and rulers, with the visuality of political virtues. She fuses private adoration with political idealization that molds heroic figures such as Manfred. We see a translation of private love, which she entertained in the domestic sphere of the castle, into the public sphere as “public love” when she attempts to express that esteem for him through tribute to that ideal. For Shelley, Despina is the creativity of love that endures, lasting like the Platonic Ideal. Her love preserves a political idealization that will outlive all passion(s). For this reason, she asks, “How can he die who is immortalized in my thoughts …, and contain eternity in their graspings” (13).

Lostendardo, on the other hand, becomes the intensity of male passion and desire that extinguishes gentler affections, and Shelley notes a moment of “impulse” within him (16). Despina notes his power to annihilate love within himself: “You are brave, and would be generous, did not the fury of your passions, like a consuming fire, destroy in their violence every generous sentiment” (15). Moreover, his hate is such that even a corrupted image of love, with the blindness of desire for political as well as personal revenge, has caused him to see how he can inflict hurt: “When she spoke of love, he thought how from that he might extract pain” (16). While Despina’s love motivates her to possess the image of Manfred within her soul and to allow that image to claim an ownership over her heart, her former lover sees her only within the emotional confines of a body subject to conquest: “[M]y heart contained [passion] as a treasure which you having discovered came to rifle” (13). In his vulgar desire, Lostendardo believes in his ability somehow to transmute a pure love into a physical one. Superimposing desire onto this passion for Despina, the general alters his love for Manfred to the passion of hate, which expresses itself in two ways; he despises Manfred for possessing Despina’s heart personally and allows his political affection to turn away along with it. For Shelley, this turn in Lostendardo becomes the love that is “twin-brother to hate” (14), for it is a frustrated and spurned love, with its passion, that now channels that intensity of feeling into a hate. Politics has the ability to change an affection into an abhorrence.

Believing in the power of love to endure and in its transformative energies, Despina attempts to revitalize new love from old for political gain: “Let your old sentiments of love for the house of Swabia have some sway in your heart. … If indeed you loved me, will you not now be my friend? … Return to your ancient faith” (14-15). Her affection for Lostendardo gives her the ability to see past the secularity of his feelings and almost to apotheosize him as much as she did Manfred: “You said you loved me; … yet if it were love, methinks that its divinity must have purified your heart from baser feelings” (15). For her, love is celestial, and its superior nature has the power to metamorphose the fleeting and earthbound nature of political sentiment. As something of a politicized Christ-like figure, she employs the language of love to deliver Lostendardo through a resurrection of a former love from his indulgence in evil and to create in him an uncorrupted spirit.

CONTRIBUTOR(S): Garrett C. Jeter

WORKS CITED

The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Ed. Esther Schor. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Friedline, Gerianne M. Glossing Romantic Commodity: "The Invisible Girl" Materialized in Mary Shelley's Short Fiction. MA Thesis. The University of Missouri. 2007. Print.

Mary Shelley. Ed. Harold Bloom. NY: Infobase Publishing, 2008. Print.

Neumann, Bonnie Rayford. The Lonely Muse: A Critical Biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. Salzburg, Austria: Institut fur Anglistik und Amerikanistik , Universitat Salzburg, 1979. Print.

Shelley, Mary. "A Tale of the Passions." Mary Shelley: Collected Tales with Original Engravings. Ed. Charles E. Robinson. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1976.

Smith, Johanna M. Mary Shelley. Ed. Herbert Sussman. NY: Twayne Publishers, 1996. Print.

Further Readings

Shelley, Mary. "A Tale of the Passions." Mary Shelley: Collected Tales with Original Engravings. Ed. Charles E. Robinson. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1976.