The Golem of Prague with RabbI Loew

Overview[]

Origins[]

The [Golem] is a legendary creature originating in European Jewish folklore with the most famous early legend being the Golem of Prague. There are numerous narratives as to the creation and outcome of the Golem.

The most famous narrative gives an account of Rabbi [Loew of Prague] , and the creation of his Golem through magical rituals using clay. The Prague story describes the creation of the Golem as inspired by a need for protection of Jewish citizens from the disastrous affects of blood [libel.] Rabbi Loew is supposed to have constructed the Golem using clay or earth, and animated it using replication of the secret/esocteric knowlegde of biblical creation of Adam. One myth describes the golem being rejected in love and then going on a violent rampage, which is similar to Shelley's plot.

Relevance to Shelley[]

The idea of the Golem in Jewish folklore predates Frankenstein. It is not clear whether Shelley intended to use this legend as a source, but there are many similarities between her monster and the Golem legend that indicate that it may have been some type of source for her work. The [wiki page on Golems] describes it as "a probable influence on Mary Shelley's Novel Frankenstein."

Rabbi Loew and Golem by Mikoláš Aleš, 1899.

Both the Monster and Golem are created from inert material, whether clay or earth in the case of the Golem or an amalgamation of dead bodies in the case of the monster. There seems to be some sort of relevance to this dead matter representing a female element of creation in both cases, even though the female body is bypassed in this form of "birth."

Golem and Monster as Metaphor for Creative Work[]

The Golem and the Monster both function as metaphors for creative works becoming independent of author's intentions once 'let loose' into the world. Chabon uses this metaphor in his pulitzer prize winning novel "The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay," and Cynthia Ozick's "The Puttermesser Papers" also include a Golem with similar themes.

The fact that Shelley refers to her text as "[hideous progeny] " connects it not only to her own monster but to the idea of her novel as an animated creature, which has an independent life of its own once published. Readers interpretation of a work is independent of authorial intention, much like the animated creature breaks free of its creator's control.

This idea of a horrible, flawed birth metaphor using the golem or monster to represent creative progeny references the concept that creative output for women was a perversion of reproductive forces. It metaphorically illustrates a perversion of creation, which in the case of Golem and Shelley's monster, escape the control of the creator and turn on them.

The golem/monster as creative metaphor, shows the novel or creative work being out of control of its creator once it is "brought to life," published or made available to the public. The lack of control of the author over the public's reaction and use of the work is an apt use of the golem/ "hideous progeny" metaphor.

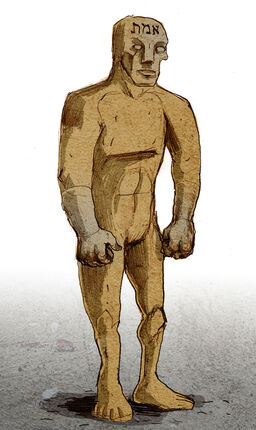

A modern depiction of a golem by fantasy artist Philippe Semeria. The Hebrew word for "truth" is written on the golem's forehead.

Hubris/challenging God/Replacing Women[]

Both the Golem and the Monster are creatures brought to life by men, bypassing the 'natural' process of biological reproduction and the necessity for human women in the creation of life. This reversal or bypassing of nature, or replication of the role of God is shown as a spiritual, ritualistic, magical process in the creation of the golem.

In contrast the process of the creation of the monster is a scientific or 'natural' one in Frankenstein. He specifically rejects older philosophers in favor of more accurate science. In both cases men are endowing inert matter with life, spirit or animating force. This can be seen as an act filled with hubris in the sense of replacing the traditional role of a biblical God in giving life to human beings. It can also be interpreted as a sexist/perverse action in the sense of reversing and bypassing the reproductive role of women in creating life.

In the case of both the Golem and Shelley's monster, the theme arises of questioning the definition of life, soul or what it fundamnetally means to be human. The legend of the Golem approaches this subject from a religious and spiritual framework, while Frankenstein is situated in the realm of science and the exploration of new physical knowledge as opposed to employing ancient esoteric secrets. The creator of the Golem must inscribe sacred letters either onto the Golem's forehead or onto paper which is placed into its mouth. There are ritualistic movements involved in the moment of bringing it to life, such as circling the Golem while reciting certain phrases. Meanwhile Shelley's novel describes the moment of creation of Frankenstein's monster as a quiet, alomst non-event. Later adaptions of her work further emphasize science - such as electricity- being used specifically in order to imbue the monster with life as opposed to magical rituals.

Reversed or "Male" Birth[]

Many Frankenstein adaptions implicitly include a homosocial relationship which produces the creature (such as that shown between Victor and male peers The Curse of Frankenstein and the sequel The Revenge of Frankenstein) This reference to male-birth enhances the idea of the monster being "born" through a process which bypasses or is a reversal of the "natural" biological process which requires a woman's body. The use of body parts to create the new being also intimates a reversal of life. In Shelley's novel this bypassing or "profane penetration" of nature by a man results in perverse destructive outcomes. The monster murders Frankenstein's loved ones and finally kills him, and so can be seen as a feminist critique of men bypassing and attempting to steal reproductive, 'natural' animating power from women.

In some versions of the Golem narrative, the Golem obeys initially in its protective role for the Jewish population before inevitably turning on its creator in a highly destructive manner. There was also the belief that the creator of a Golem imbued them with part of their own essence, much as God imparted some of his self into Adam at the moment of creation.

Golem and Creature as Metaphor of Othering[]

Clay Golem reproduction

Both the Golem and Shelley's creature function as metaphorical representations of the experience of being "othered" or dehumanized. The way Jewish peoples have been persecuted over a long period of time may be tied to their creation of the mythical concept of the golem, which is dehumanized, soulless person. This myth may be viewed as an expression of the experience of victimization or persecution, especially in light that it arose during the period when Jews were persecuted falsely for blood libel.

Similarly, Mary Shelley experienced the othering that was a result of the inherent gender roles of her time, even as an upper middle class woman. Her novel and the creature within it may be viewed similarly to the Jewish creation of the Golem- as an expression of what it is to be almost human, but foreign. Such an interpretation of Shelley's work is reinforced by characters such as Safie, a literally "foreign" woman whose narrative occurs in the literal center of the plot. So in both Cases, the Golem and Shelley's monster act as vehincles to express dehumainzation.

Interplay between the Golem and Frankenstein in Adaptions[]

Very little information is available on the use of Golem style creatures in adaptions of Frankestein. However there are many Golem stories in modern Jewish American literature which intersect with Frankenstein. The Puttermesser Papers by Cynthia Ozick uses the first female Golem, created by a woman, which brings both the Jewish cultural expression of Othering and possibly Shelley's expression of dehumanizing gender related experiences together.

One noticeable interaction between Frankenstein adaptions and the Golem can be seen in the 1931 film [[1]] where Boris [Karloff's] costume design is directly influenced by the appearance of the Golem. His square-ish forehead and clay textured skin is reminiscent of the Golem.

Academic Discussion of the Golem and Frankenstein Narrative[]

Sources and Further Reading[]

Boris Karloff Costume design influenced by the Golem

[Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay]

[Libel]

[http:// http://0-www.jstor.org.library.uark.edu/stable/689735 Toumey, Christopher P.. “The Moral Character of Mad Scientists: A Cultural Critique of Science”.Science, Technology, & Human Values 17.4 (1992): 411–437. Web...]

A Prague reproduction of the Golem

"Golem." My Jewish Learning. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2016.(link)

"Golems, Flesh: Frankenstein, Undead." Golems, Flesh: Frankenstein, Undead. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2016. (link)

"Blood Libel: A False, Incendiary Claim against Jews | ADL." ADL. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2016.(link)

Mellor, Anne K. "Mellor, "My Hideous Progeny"" Mellor, "My Hideous Progeny" N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2016. (link)

Rowen, Norma. "Rowen, "The Making of Frankenstein's Monster"" Rowen, "The Making of Frankenstein's Monster" N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2016. (link)

Knight, Rhonda. Worlds without End. N.p., n.d. Web. 3 Mar. 2016. (link)

Kakoudaki, Despina. Anatomy Of A Robot: Literature, Cinema, And The Cultural Work Of Artificial People. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2014. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 3 Mar. 2016. (link)

Baer, Elizabeth R. The Golem Redux: From Prague To Post-Holocaust Fiction. Detroit, MI: Wayne State UP, 2012. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 3 Mar. 2016. (link)

Anolik, Ruth Bienstock. "Reviving The Golem, Revisiting Frankenstein: Cultural Negotiations In Ozick's The Puttermesser Papers And Piercy's He, She And It." Connections and Collisions: Identities in Contemporary Jewish-American Women's Writing. 139-159. Newark, DE: U of Delaware P, 2005. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 3 Mar. 2016. (link)